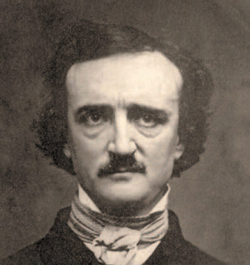

Edgar Allan Poe

In 1776, at the start of the American Revolution, when seemingly unstoppable British naval forces attacked the fledgling fort at the island’s southern tip, they were repelled by colonists under Col. William Moultrie.

And as the impending Civil War approached, federal troops abandoned Fort Moultrie, named for its Revolutionary War commander, for what they thought would be a stronger position at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The following April, Confederate guns pounded Sumter into submission, plunging the young country into a brother-against-brother war that would drag on for four more brutal years.

Between the two wars, Sullivan’s Island was home to a soldier who had not yet reached his 19th birthday when the Army assigned him to Fort Moultrie in November 1827 and had, for whatever reason, signed up for military duty under an assumed name. Edgar Allan Poe, America’s master of the macabre, had already published his first book of poetry when he enlisted as Edgar A. Perry. Poe’s formal education was interrupted when he was booted from the University of Virginia, apparently after running up heavy gambling debts. He spent 13 months at Fort Moultrie before cutting short his five-year enlistment and enrolling at the United States Military Academy. A year or so later, he was dishonorably discharged from West Point.

Though Poe spent only a year and a month in the Lowcountry, he left his mark on Sullivan’s Island – and the island apparently had quite an effect on him, as well, providing the setting for at least three of his stories: “The Gold Bug,” “The Balloon Hoax” and “The Oblong Box.” This is how he described Sullivan’s Island in “The Gold Bug”:

“This island is a very singular one. It consists of little else than the sea sand and is about three miles long. Its breadth at no point exceeds a quarter of a mile. It is separated from the mainland by a scarcely perceptible creek, oozing its way through a wilderness of reeds and slime, a favorite resort of the marsh hen. The vegetation, as might be supposed, is scant or at least dwarfish. No trees of any magnitude are to be seen. Near the western extremity, where Fort Moultrie stands and where are some miserable frame buildings, tenanted, during summer, by the fugitives from Charleston dust and fever, may be found the bristly palmetto; but the whole island, with the exception of this western point and a line of hard, white beach on the seacoast, is covered with a dense undergrowth of the sweet myrtle …”

Poe’s mother and father, both performers, died at an early age, leaving three young children. Poe was raised by Richmond, Virginia, merchant John Allan, but his relationship with his foster father soured when he was forced from the University of Virginia. Alcoholism and a drug problem plagued Poe throughout his dark and mysterious life. His first wife succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 18, five years after their marriage, and was the subject of his poem, “Annabel Lee.”

Poe died in Baltimore in 1849. Though he was only 40 when the curtain closed on his life and though he spent only 13 months on Sullivan’s Island, his legacy remains. Three streets, Gold Bug Avenue, Raven Drive and Poe Avenue, hark back to him and his works, and Gold Bug Island, across the Intracoastal Waterway in Mount Pleasant, is another testament to the eternity of his writing and poetry. And Poe’s Tavern on Middle Street, also named in his honor, offers fare reminiscent of the island’s early years. The menu includes hamburgers with names such as Gold Bug, Pit & Pendulum, Annabelle Lee, Tell-Tale Heart and, a fitting tribute to Poe’s time on the island, Starving Artist.